written and photographed by Mary L. Peachin

Jun 1999, Vol. 3 No. 8

“Saddle up and head ’em out!” Quoting an old wrangler, Tim Singewald, owner of Bridger Wilderness Outfitters and the historic DC-Bar Guest Ranch in Pinedale, Wyoming, added, “We’re burning daylight.” Singewald, our trailboss for the week, was about to lead seven of us on a 125-mile, seven-day horseback ride taking that took us the length of the Wind River Range in the Bridger Wilderness of Wyoming.

“Saddle up and head ’em out!” Quoting an old wrangler, Tim Singewald, owner of Bridger Wilderness Outfitters and the historic DC-Bar Guest Ranch in Pinedale, Wyoming, added, “We’re burning daylight.” Singewald, our trailboss for the week, was about to lead seven of us on a 125-mile, seven-day horseback ride taking that took us the length of the Wind River Range in the Bridger Wilderness of Wyoming.

More than a 100 years ago, Congress declared the Bridger Wilderness as one of the country’s first national forests. Gannett, the highest peak in Wyoming, reaches an elevation of 13,804 feet. The Wind River Range, which straddles the Continental Divide, has six of the seven largest glaciers in the continental U. S, and is the home of Gannett, the highest peak in Wyoming (13,804 feet). Besides being an ideal riding location, the area features cutthroat, brook, and the rare, species of high-elevation golden trout (which are found only at elevations this high), making many of the range’s 1300 lakes ideal for fishing.

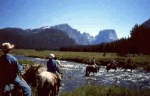

Lighting his Cheroot cigar, Singewald signaled and we were off, our horses setting off from the trip on the Green River trailhead following along the Highline Trail. Tall and lean,the former banker exuded confidence that came from 14 years of experience in guiding , hunting, fishing, and horsepack trips throughout Wyoming. Besides Singewald, our group of eight was supported by three wranglers who helped us care for the quarter horses and and eight pack mules (featuring names such as Jesse, Pauline, and Tyrell)that carried our camping gear and food.

Lighting his Cheroot cigar, Singewald signaled and we were off, our horses setting off from the trip on the Green River trailhead following along the Highline Trail. Tall and lean,the former banker exuded confidence that came from 14 years of experience in guiding , hunting, fishing, and horsepack trips throughout Wyoming. Besides Singewald, our group of eight was supported by three wranglers who helped us care for the quarter horses and and eight pack mules (featuring names such as Jesse, Pauline, and Tyrell)that carried our camping gear and food.

Packing into the wilderness on a horse allows the horse to carry your camping gear, and the opportunity to bring more food than you might if carrying the load on your back. Many horseback trips have a space from which they ride each day. This eliminates the work of setting up camp as we had to do each night.

Spring arrived late in Wyoming that year; as we set off in mid-July, the snowmelt hadn’t begun in at the higher state’s higher elevations. Seeing the still-solid snowpack, Singewald decided to reverse the direction of our trip, by first tackling the higher snow-covered passes in the north. His reasoning: If we had departed, as originally planned, from the southern Big Sandy trailhead, we would have been five days into the ride before reaching the snow-packed passes near Green River. If the horses could then not make it through that more treacherous terrain, we would not have enough provisions to backtrack to the southern trailhead.

Spring arrived late in Wyoming that year; as we set off in mid-July, the snowmelt hadn’t begun in at the higher state’s higher elevations. Seeing the still-solid snowpack, Singewald decided to reverse the direction of our trip, by first tackling the higher snow-covered passes in the north. His reasoning: If we had departed, as originally planned, from the southern Big Sandy trailhead, we would have been five days into the ride before reaching the snow-packed passes near Green River. If the horses could then not make it through that more treacherous terrain, we would not have enough provisions to backtrack to the southern trailhead.

A few hours into the first day, We put on our slickers as the an afternoon rain shower muddied the trail. The rain increased, until, as we forded the glacial water of the Green River, the swift current briefly swept a horse named Dusty and his rider, the only child (10 years old) in our group, downstream. Although the horse and rider righted themselves and were soon safe, Singewald’s concern heightened when the peaks of of the Green River Ppass came into view: snow blanketed the mountain from top to bottom.

We kept going, though, moving slowly and leaning forward to make it easier for the horses to climb the rocky terrain. We were successful in crossing several patches of snow. Suddenly, Singewald’s horse, which led the group, fell through the a patch of ice glazing the snowpack. He was able to get his horse up, but after that experience he decided to take a detour and “bushwhack,” avoiding the crusty snow on the slope of the pass.

We kept going, though, moving slowly and leaning forward to make it easier for the horses to climb the rocky terrain. We were successful in crossing several patches of snow. Suddenly, Singewald’s horse, which led the group, fell through the a patch of ice glazing the snowpack. He was able to get his horse up, but after that experience he decided to take a detour and “bushwhack,” avoiding the crusty snow on the slope of the pass.

We rode on for another hour. As we reached an elevation of 11,200 feet near Near Elbow Peak, the snow blanketed the entire mountain trail. We would no longer have the option of “bushwhacking” around patches. In the next few hours, as we carefully worked our way onward, Three more horses, including my horse, Salmon, broke through the crust of the hard-packed snow. The sharp rocks , buried under the white snow cut the legs of the horses. After eight hours, the horses were hurting, the riders were weary, and everyone was more than a bit tense.

The day did improve, however; after successfully navigating the high passes, we began to feel more relaxed as we descended from the barren landscape of Hat Pass, past the treeline, and through flowering meadows flanked by views of mountains and lakes. We stopped to tend the horses, then camped that night in a beautiful glen located near a waterfall. Once we descended below the barren landscape above the tree line, we rode through flowering meadows with views of scenic mountains and lakes.

The day did improve, however; after successfully navigating the high passes, we began to feel more relaxed as we descended from the barren landscape of Hat Pass, past the treeline, and through flowering meadows flanked by views of mountains and lakes. We stopped to tend the horses, then camped that night in a beautiful glen located near a waterfall. Once we descended below the barren landscape above the tree line, we rode through flowering meadows with views of scenic mountains and lakes.

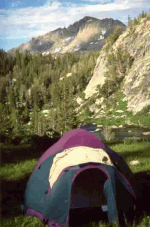

Luckily, we got into the waterproof tents before the deluge began. Thunder boomed and lightning boomed and crackled as hail and rain pounded our tents during the night.

The “yip” of the wranglers calling in the mules for packing came too early that the next morning. We would spend the day ridinge seven hours through Lester and Baldy Ppasses, again at elevations exceeding 11,000 feet. As before, magnificent views continued to distract us from the hard riding and long hours in the saddle. The Wind range is scenically dotted with small lakes and tall ridges that few has the ability to see in depth.

Two hours of each day were spent making and breaking camp. Each night the wranglers rounded up the horses, corralling them inside a transportable solar-powered electric fence, which prevented them from straying. Some horses were hobbled for the night. Each day riders was were responsible for saddling and unsaddling their our horsess and setting up their own our tents at each campsite.

Two hours of each day were spent making and breaking camp. Each night the wranglers rounded up the horses, corralling them inside a transportable solar-powered electric fence, which prevented them from straying. Some horses were hobbled for the night. Each day riders was were responsible for saddling and unsaddling their our horsess and setting up their own our tents at each campsite.

We would look for a nearby stream to rinse off our bodies and on one occasion, we jumped into a lake. While it felt great to remove the dust of the trail, the water was so icy, we never again fully submerged our bodies.

The cooking wasn’t fancy, but there was plenty of food. After breakfast-bacon, eggs, or pancakes-we would each make a sandwich, packing them in our saddlebags for a picnic lunch at a scenic spot along the trail.

The cooking wasn’t fancy, but there was plenty of food. After breakfast-bacon, eggs, or pancakes-we would each make a sandwich, packing them in our saddlebags for a picnic lunch at a scenic spot along the trail.

Each night, we hovered around a cozy campfire for and enjoyed dinnermeals. Nathan, our wrangler-cook, served up some mighty fine trail-fare that included hamburgers, pork chops, steak, and pasta. In the evening, the wranglers recited cowboy poetry while we passed around a flask of Yukon Jack, pouring it into our Sierra tin cups to sip. We spun a few yarns about past adventures as we sat around the campfire, then found our tents and fell into a deep sleep.

On the third and fourth days we continued to descend, and the trail became scattered with rocks and lined with boulders. One horse slid on a rock, while another got his shoe wedged between rocks. Luckily, Singewald and the well-trained wranglers were able to pry the horse’s leg hoof from the rocks without it panicking or breaking a leg. They gently nuzzled the horse and they freed up the leg.

That night, as we rode into our campsite at North Fork Lake, the sky began to darken. Wwe had just set up our tents when a severe storm erupted-lightning, thunder, and high winds raged for about three hours. That night we ate standing up, huddled shivering as we huddled under a tarp. The temperature dropped so low the water in our drinking bottles froze, and we fell asleep huddled under blankets in our tents. Luckily, this was the worst weather we saw during the whole trip, and the storm passed by morning, leaving us with cold, crisp sunlight for the last two days of the journey.

That night, as we rode into our campsite at North Fork Lake, the sky began to darken. Wwe had just set up our tents when a severe storm erupted-lightning, thunder, and high winds raged for about three hours. That night we ate standing up, huddled shivering as we huddled under a tarp. The temperature dropped so low the water in our drinking bottles froze, and we fell asleep huddled under blankets in our tents. Luckily, this was the worst weather we saw during the whole trip, and the storm passed by morning, leaving us with cold, crisp sunlight for the last two days of the journey.

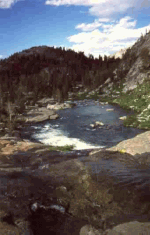

We rode on through lower and lower elevations, the scenery growing more lush with every mile. The lakes and river streams ranged from glacial green to sapphire blue. Once we descended below the tree line, the landscape was filled with spring flowers: lupine, Indian paintbrush, monkey’s hand, elephant head, daisies and dandelions bloomed in the late snow. There were beautiful vistas, including a favorite of rock climbers, the Cirque of Towers.

Near the trailhead to the Wind River Range, we began to see backpackers along the trail. Although the terrain was too rugged for most hikers to reach the interior of the wilderness, the closer parts of the range are popular for hiking. As the number of backpackers increased, we knew we were nearing our the take-out trailhead.

In seven days, our 125-mile route had taken us from Green River Lake to Big Sandy trailhead. We had climbed five passes: Green River, Elbow, Lester, Baldy, and Hat. Our We’d camped at campsites included Green River, Big Water Slide, Timico Lake, Prue Lake, Raid Lake, and the East Fork River. We had jumped into the icy waters of Timico lake, and eased carefully into the waterfalls at Big Water Slide and the East Fork River to cleanse our bodies.

The ride was a true wilderness experience:. We lived in the same blue jeans for a week and put mosquito netting over our heads at twilight. We ate and sleep on the ground. We lived in dirty clothes, falling asleep to the scent of horse in that permeated our tents. We listened to the sound of tinkling cowbells, worn by the mules at night. Our reliable horses carried us over a variety of terrain of snow,rock, and mossy bogs. We forded rivers, creeks, and one shallow lake. The lakes and river streams ranged from glacial green to sapphire blue.

The ride was a true wilderness experience:. We lived in the same blue jeans for a week and put mosquito netting over our heads at twilight. We ate and sleep on the ground. We lived in dirty clothes, falling asleep to the scent of horse in that permeated our tents. We listened to the sound of tinkling cowbells, worn by the mules at night. Our reliable horses carried us over a variety of terrain of snow,rock, and mossy bogs. We forded rivers, creeks, and one shallow lake. The lakes and river streams ranged from glacial green to sapphire blue.

Once we descended below the tree line, the landscape was filled with spring flowers: lupine, Indian paintbrush, monkey’s hand, elephant head, daisies and dandelions bloomed in the late snow. There were beautiful vistas, including the favorite of rock climbers, the Cirque of Towers.

Was it an adventure? You bet it was! Definitely, and not one for the novice, one for experienced riders, those comfortable with horses and long hours spent in the saddle. There was no complaining on this trip. Despite the hardship, or perhaps in part because of it-our group grew close over the week we spent in the wilderness. The bond grew to include not only the trip leaders and guests, but also the horses and even the mules-a small group that had together made a journey. There was a unique bonding between the riders, horses, and even with our mules; Jesse, Pauline, and Tyrell.