Written and photographed by Mary L. Peachin

Vol. 10 No. 2

“There are two kinds of penguins in the Antarctic, the white ones coming towards you and the black ones going away from you.”-Anonymous

“There are two kinds of penguins in the Antarctic, the white ones coming towards you and the black ones going away from you.”-Anonymous

Antarctica’s penguin highway is one of nature’s great two-lane, gridlocked non-stop traffic rush hours. Unfortunately, this incredible sight is not readily accessible. Icy penguin trails curve, meander, detour, then disconnect through treacherous terrain following a path frequently obscured by snow or cloud cover.

Penguins inhabit an environment so inhospitable that there is a only a three month—December through February—window when daylight hours or “summer” conditions melt enough of the ice pack to allow ship navigation. But, for many, the 600 miles of open violent ocean of the Drake Passage, deters them from visiting the penguin highway of the Southern Continent.

During the Passage in 30 foot seas, we tightly gripped the sides of our beds for security. Unsecured objects flew across the cabin. By morning, the majority of 110 passengers were so seasick they wished they were dead or someone would mercifully shoot them. A woman, toting a handful of barf bags into the sparsely occupied dining room, projectally erupted. She cleared the room as if she was spreading a contagious disease.

During the Passage in 30 foot seas, we tightly gripped the sides of our beds for security. Unsecured objects flew across the cabin. By morning, the majority of 110 passengers were so seasick they wished they were dead or someone would mercifully shoot them. A woman, toting a handful of barf bags into the sparsely occupied dining room, projectally erupted. She cleared the room as if she was spreading a contagious disease.

Finally, at mid-afternoon on the second day –landfall! We made the first of many wet beach landings. Sliding from the pontoon of the zodiac onto the beach, our legs were protected from the frigid water by rain pants and rubber boots.

The penguin highway traverses steep, snowy terrain them sometimes simply follows the easy walk of a beach. Shivering in below freezing cold became irrelevant. We were surrounded by penguins, eyes glued to binoculars or camera shutters clicking, as we followed their web-footed path.

At Aitcho Island in the South Shetland Archipelago of the Weddell Sea, colonies of chinstrap penguins hunkered on the beach. A distinctive narrow band of black feathers artistically extends from ear to ear under their chin. Rocks were covered with the ammonia-like, fishy stench of guano and skeletal whale bones littered the beach. It is thought that white guano indicates that penguins have dined on fish or squid. If it’s pink, they’ve gorged on krill. Three or more days without food, it turns greenish in color.

At Aitcho Island in the South Shetland Archipelago of the Weddell Sea, colonies of chinstrap penguins hunkered on the beach. A distinctive narrow band of black feathers artistically extends from ear to ear under their chin. Rocks were covered with the ammonia-like, fishy stench of guano and skeletal whale bones littered the beach. It is thought that white guano indicates that penguins have dined on fish or squid. If it’s pink, they’ve gorged on krill. Three or more days without food, it turns greenish in color.

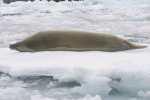

Here, penguins shared the beach with lazing three ton 12-foot elephant seals. The bull, known as the “beach master,” can mate with as many as 100 females, but he must fight the other bulls for domination and the right to service his harem. Occasionally, a whiskered head would rise to yawn or snarl at another. In the 1800s, these creatures were almost wiped to extinction solely for their oil.

Many of the brush-tailed chinstrap penguins had week old chicks. Penguins lay two eggs, but in many cases, only one chick will survive. Sleek and fast underwater swimmers, like all penguins, they waddle clumsily on land. Squawking exchanges between males and females appear related to taking turns nesting and nurturing the chicks. It’s difficult to distinguish between sexes. Males diligently pick pebbles on the beach or attempt to steal from another nest to compulsively tidy their nest.

Many of the brush-tailed chinstrap penguins had week old chicks. Penguins lay two eggs, but in many cases, only one chick will survive. Sleek and fast underwater swimmers, like all penguins, they waddle clumsily on land. Squawking exchanges between males and females appear related to taking turns nesting and nurturing the chicks. It’s difficult to distinguish between sexes. Males diligently pick pebbles on the beach or attempt to steal from another nest to compulsively tidy their nest.

Gentoo’s might gather 3000 pebbles, while the Adelie (named for a French explorer’s wife) may collect a mere 300 stones. Like any nursing infant, the chick, fluffy rump sticking out with its head snuggled under the warmth of the parents breast, will emerge to nibble the parent’s orange beak for a regurgitated meal.

Brown Bluff, at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, has a colony of approximately 25,000 black-headed Adelie and gentoo penguins. The size of these chicks and their growing appetites required both parents to hunt for krill. In groups, they waddled to the edge of the water then spontaneously, as if on queue, synchronically plunged into the ocean. Allegedly, the penguin in the front is pushed, and if a leopard seal doesn’t attack it, the other penguins feel safe to enter the water.

Brown Bluff, at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, has a colony of approximately 25,000 black-headed Adelie and gentoo penguins. The size of these chicks and their growing appetites required both parents to hunt for krill. In groups, they waddled to the edge of the water then spontaneously, as if on queue, synchronically plunged into the ocean. Allegedly, the penguin in the front is pushed, and if a leopard seal doesn’t attack it, the other penguins feel safe to enter the water.

For the novice, it’s difficult to differentiate between gentoo and Adelie species. Gentoo have a subtle white spot on their crown, while Adelie have small white rings around their eyes. Expedition leader, Tom Ritchie compares penguins to tubby little people in formal attire. They walk upright, and stumble over and slip on ice, just like people.

The “Devil”, discovered by Swedish explorer Otto Nordenskjold in 1901, has a breeding colony of 10,000 Adelies. These penguins waddled up a cliff leaving a pattern in the snow like the etched icy trail of a skier.

The “Devil”, discovered by Swedish explorer Otto Nordenskjold in 1901, has a breeding colony of 10,000 Adelies. These penguins waddled up a cliff leaving a pattern in the snow like the etched icy trail of a skier.

Most of us were asleep when Tom Ritchie announced the rare sighting of Emperor penguins. The ship edged slowly along a tall, tabular glacier cracked with deep crevasses as it approached the taller three-foot penguins. Crunching ice rattled the re-enforced hull as we excitedly huddled on the bow watching two Emperors followed by an Adelie plunge into the frigid water. Shy and eager to get away from us, they slid or “tobogganed” on their chest carving a trail to the water’s edge. Throughout the morning, we continued to have Emperor sightings. We had the unique experience of observing two fluffy and one molted chick.

Sighting an Emperor penguin seldom happens because mating occurs deep in the ice pack during the dark, intolerable Antarctic winter. Nesting males endure harsh conditions by almost starving for three months, while females hunt food at sea. During this time frame, the ice continues to pack making the distance to water as far as 100 miles. Females return when the chicks are born. They feed their newborn as the famished males toboggan and waddle to water’s edge to satiate their hunger.

Sighting an Emperor penguin seldom happens because mating occurs deep in the ice pack during the dark, intolerable Antarctic winter. Nesting males endure harsh conditions by almost starving for three months, while females hunt food at sea. During this time frame, the ice continues to pack making the distance to water as far as 100 miles. Females return when the chicks are born. They feed their newborn as the famished males toboggan and waddle to water’s edge to satiate their hunger.

Lindblad naturalists believed their first sighting of three chicks, old enough to have been abandoned by their parents, occurred because the edge of their ice flow broke away. Nearby, a 12-foot spotted leopard seal, a ferocious predator, lay in wait on another iceberg. Hopefully, the fluffy chicks would mature by molting in the next week, enabling them to swim to safety.

At Madder Cliffs on Joinville island, 50,000 Adelie, gentoo, and chinstrap penguins nested on snowy patches, offshore rocks, and high on the steep slopes of the red rock island. Surrounding the colony were snow white pigeon-sized sheathbills, the only Antarctic bird without webbed feet. This bird is the “hyena” of the continent scavenging everything from guano to corpses. Sheathbills and brown skuas prey on both eggs and newborn chicks.

At Madder Cliffs on Joinville island, 50,000 Adelie, gentoo, and chinstrap penguins nested on snowy patches, offshore rocks, and high on the steep slopes of the red rock island. Surrounding the colony were snow white pigeon-sized sheathbills, the only Antarctic bird without webbed feet. This bird is the “hyena” of the continent scavenging everything from guano to corpses. Sheathbills and brown skuas prey on both eggs and newborn chicks.

Humpbacks, attracted to the same dense krill plankton diet of the penguin spy hopped to peek at us, finned as if waving, then tailed as they sounded.

Bailey Head on Deception Island is a composite of volcanic calderas. It features a natural amphitheater with a unique “penguin highway.” Spotless birds returning from the sea walk on the right side of the path, while dirty penguins heading to the sea, pass on the left in this 100,000 pair gentoos colony.

Swimming in the Antarctic? If the penguins are so adept, well, why not give it a try? First, the expedition pitched in to build a “swimming hole” on the beach in Whalers Bay. A better description might be a muddy hole heated by fumaroles or sulphuric-smelling steam rising from the flooded center of the crater.

Swimming in the Antarctic? If the penguins are so adept, well, why not give it a try? First, the expedition pitched in to build a “swimming hole” on the beach in Whalers Bay. A better description might be a muddy hole heated by fumaroles or sulphuric-smelling steam rising from the flooded center of the crater.

Whalers Bay or Port Foster was a Norwegian whaling station in 1900. The beach is scattered with whale skeletons, rusted metal shelters, and broken remnants of wooden boats used to carry water. Hiking the steep saddle of Neptune’s Window gave us a feeling of appreciation of the challenging climbs made by penguins.

40-knot catabatic winds swirled clouds of snow down the glacier in Neko Harbor. No big deal for the penguins. They turn their thick layer of blubber and feathers against a wind strong enough to knock us off our feet.

40-knot catabatic winds swirled clouds of snow down the glacier in Neko Harbor. No big deal for the penguins. They turn their thick layer of blubber and feathers against a wind strong enough to knock us off our feet.

The penguin’s black and white counter shading provides camouflage and also helps control their temperature. Like mammals, they are warm blooded birds who spend many hours preening themselves. From a gland just above their stiff tail feathers, preening replenishes a warm layer of oil on their coat. Nasal glands at the base of their bills allow them to excrete excess salt from sea water.

Kayaking in the Antarctica offers the unique opportunity for an eye level view of the sleek swimming penguin. At Cuverville Island, located in the middle of the Errera Channel between Ronge Island and the Arctowski Peninsula on the mainland, we admired the compact, streamlined, short bodies of the penguins from kayaks. Stiff wings attached to strong muscles are used for propulsion. Feet and stubby tails serve like a rudder. Like a flipper, it thrusts them forward with an upward stroke of their wing.

Kayaking in the Antarctica offers the unique opportunity for an eye level view of the sleek swimming penguin. At Cuverville Island, located in the middle of the Errera Channel between Ronge Island and the Arctowski Peninsula on the mainland, we admired the compact, streamlined, short bodies of the penguins from kayaks. Stiff wings attached to strong muscles are used for propulsion. Feet and stubby tails serve like a rudder. Like a flipper, it thrusts them forward with an upward stroke of their wing.

The penguins, totally unconcerned about us on land, were afraid of the yellow kayaks. Water is the one place where they are vulnerable to predation. Porpoising out to sea, they left trails of guano floating in the water.

We watched Adelie’s jump in the water and occasionally glimpsed one gracefully speeding under the kayak, white feathers gleaming in the clear visibility of the water. Pack ice crackled like rice crispies, air escaping through its density.

We watched Adelie’s jump in the water and occasionally glimpsed one gracefully speeding under the kayak, white feathers gleaming in the clear visibility of the water. Pack ice crackled like rice crispies, air escaping through its density.

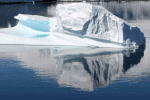

Grounded and floating icebergs were shaped and colored with different shades of deep blue glacial ice. The experience was magical.

The low positioned legs of the penguin may minimize drag in the water, but force them to waddle in an upright stance on land. Appearing clumsy and awkward, they are really quite agile. Three yellow hooked webbed toes grip slippery rocks and ice. For an additional hold, they will occasionally use their beaks.

Returning north, the mile-wide Lemaire Channel, located between the mainland and Booth Island, is considered one of the most beautiful places in the Antarctic. Its seven miles are hemmed by high, steep, glaciated snow-covered mountains.

Antarctic expeditions offer the adventurer onshore, up close opportunities to observe three or four of the seventeen species of flightless birds. Here, in an icy wonderland in magnificent scenery are footprints in the snow, those of the penguin highway.

Lindblad Expeditions, www.expeditions.com