written and photographed by Mary L. Peachin

Dec 2002, Vol. 7 No. 3

Motoring along the Chagres River, the skiff passed under a historic bridge used by the railroad to build the Panama Canal. Elercido Parazo, a native of the nearby Chocoe village, headed the skiff to Lake Gatun where we planned to fish for peacock bass known as Sargento. As we rolled over wakes from freighters approaching the Pablo Miguel locks, we passed the infamous Gaillard Cut of the Panama Canal. It’s the narrowest section of the canal (800 feet wide), and its excavation proved to be deadly.

Motoring along the Chagres River, the skiff passed under a historic bridge used by the railroad to build the Panama Canal. Elercido Parazo, a native of the nearby Chocoe village, headed the skiff to Lake Gatun where we planned to fish for peacock bass known as Sargento. As we rolled over wakes from freighters approaching the Pablo Miguel locks, we passed the infamous Gaillard Cut of the Panama Canal. It’s the narrowest section of the canal (800 feet wide), and its excavation proved to be deadly.

Elercido, who guides fishing trips for Gamboa River Resort made a few stops during our forty-minute boat ride into the rainforest. Crocodiles and turtles sunned on muddy banks or logs. Picking a few bean-like guava fruit, Elercido stopped to feed two white-faced Capuchin monkeys. Interrupted from stripping bark of dead trees to eat termites, they eagerly grabbed the welcomed treat.

Birds were busy fishing. An eagle soared overhead while a cormorant-like black anhinga and a osprey perched on a log eyeing the water. Elercido pointed to white eggs attached above water level to stalks of cane. Speaking in Spanish, “those are caracola (snail) eggs. They hatch at night when the eagle can’t see to eat them.

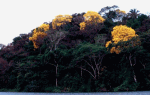

As the boat navigated the shallow channels of the dense forest, we admired the yellow blossom of the guayacan or Golden Shower tree, and the less abundant purple blooms of the jacaranda tree. The Philodendron, ferns, bromeliads, orchids, and scheflera plants were larger than any houseplants. Liana vines draped from huge strangler fig trees. The distinctive growling of howler monkeys echoed through the jungle. Wherever we stopped to fish, a small duck-like red beak wattled jacana swam around the boat looking for a fish handout.

As the boat navigated the shallow channels of the dense forest, we admired the yellow blossom of the guayacan or Golden Shower tree, and the less abundant purple blooms of the jacaranda tree. The Philodendron, ferns, bromeliads, orchids, and scheflera plants were larger than any houseplants. Liana vines draped from huge strangler fig trees. The distinctive growling of howler monkeys echoed through the jungle. Wherever we stopped to fish, a small duck-like red beak wattled jacana swam around the boat looking for a fish handout.

But there was none to give him. The water level was low, the water warm, and the fishing was not good. Elercido caught one small peacock bass. Too small to display its rainbow of color, it sported the typical black spotted tail.

Gamboa River Resort, about 30-minutes from Panama City, is located in Parque Nacional Soberania. Embraced by the jungle, the region is designated as an Eco-reserve. A hillside tram carries bird watching visitors above the canopy. The resort has nature exhibits and a diorama featuring the indigenous people of Panama. There are hiking trails and kayaks are available for rental at the marina. Beautifully designed rooms surround a two-story lobby designed with towering plants from the jungle.

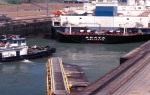

Today, this engineering feat, now operated independently by the Panama Canal Authority, remains the primary attraction for visitors to Central America’s southernmost republic. Outside the city limits of Panama City are the famous Miraflores Locks, which level the water for ships passing through the 80-mile Panama Canal. The memory of 22,000 French dying from epidemics of malaria and yellow fever is marked in a nearby cemetery where simple crosses mark gravestones; each representing 100 dead canal workers.

Today, this engineering feat, now operated independently by the Panama Canal Authority, remains the primary attraction for visitors to Central America’s southernmost republic. Outside the city limits of Panama City are the famous Miraflores Locks, which level the water for ships passing through the 80-mile Panama Canal. The memory of 22,000 French dying from epidemics of malaria and yellow fever is marked in a nearby cemetery where simple crosses mark gravestones; each representing 100 dead canal workers.

The history of the city is equally fascinating. In 1671, Captain Henry Morgan viewed Panama City from the top of a nearby hill now called Cerro Luisa. Not only could he see the city, he also had a view of the Pacific and the Caribbean. Today, the remaining ruins have been established as a park. The tall pink lilac-type flowering guayaca tree surrounds the ruins. There is a small museum next to the park.

Another view of the city and the Pacific coastline is from the Metropolitan Pargue Nacional. Of the 2.8 million people in Panama, seven indigenous people remain, there are three ethnic groups of Latinos, and numerous Chinese.

The old quarters of Casco Antigua or Colonial Panama was rebuilt 10 years after the fire. The old wrought iron colorfully painted balconies, many decorated with bougainvillea, extend across the narrow streets. The area reminds one of the French Quarter in New Orleans. Tourist season in Panama is the dry season months of November to April. An hour away, the city of Colon (pop.120,000)is the busiest port in Panama. Its primary industry is shipping containers to port destinations around the world.

The old quarters of Casco Antigua or Colonial Panama was rebuilt 10 years after the fire. The old wrought iron colorfully painted balconies, many decorated with bougainvillea, extend across the narrow streets. The area reminds one of the French Quarter in New Orleans. Tourist season in Panama is the dry season months of November to April. An hour away, the city of Colon (pop.120,000)is the busiest port in Panama. Its primary industry is shipping containers to port destinations around the world.

But, the Panama Canal is only a small taste of a country offering a fascinating culture, a fascinating rainforest, villages framed with boundless hedges of multi-colored veraneras or bougainvillea’s, the yellow blossom of the guayacan tree, and the white flower of the Caracucha.

In recent years, Panama has built a tourist infrastructure of fine hotels and restaurants. Driving two hours west from Panama City on the Carretera Interamericana (Pan-American Highway), a driver, guide and I drove to the region known as El Valle. At the Capira turnoff, a small bakery, Queso Chela, sells hot homemade empanadas. The roadway market is always jammed with cars, horns honking, jockeying for the few parking places.

El Valle de Anton, has a Sunday craft market featuring Panama hats, baskets woven by the Emberá. One side of the outdoor market includes vendors selling freshly picked fruit, vegetables, and flowers. Surrounded by mountains, the basin of valley is an extinct volcano.

El Valle de Anton, has a Sunday craft market featuring Panama hats, baskets woven by the Emberá. One side of the outdoor market includes vendors selling freshly picked fruit, vegetables, and flowers. Surrounded by mountains, the basin of valley is an extinct volcano.

At Chorro Macho Falls, the adventurous can rappel over the canopy of the rainforest admiring a 150-foot waterfall. Visitors can also swim in the park’s spring fed pool. Located a mile down the road is El Nispero zoo. Although different from the open enclosure exhibits of United States zoos El Nispero offers a remarkable collection of unique birds, animals, capybara, and tropical flowers.

deCameron resort is located several hours northwest of El Valle near the city of Farallon. A stunning view of the sparkling waters of the Gulf of Panama can be seen through the entrance of the lobby. The resort has six restaurants, offers many beach sports, has several swimming pools, and its rate is all-inclusive including alcoholic beverages.

Returning the next day to Panama City, a three-hour drive, we ate at a small typical restaurant named La Pollera. The chef features Sancocho, a homemade chicken soup with white yam and cilantro. Another typical dish is rice with chicken and coconut, and plantains in a sweet Carmel sauce.

Returning the next day to Panama City, a three-hour drive, we ate at a small typical restaurant named La Pollera. The chef features Sancocho, a homemade chicken soup with white yam and cilantro. Another typical dish is rice with chicken and coconut, and plantains in a sweet Carmel sauce.

In the center of the city, Pedrarías Dávila founded Panama Viejo (old) in 1519. The city thrived as a silver route from Peru continuing on the Camino Real (Royal road) to port of Portobella where bullion was loaded on ships headed for Europe.

A motorized piragua or dugout canoe charged us $3.00 for the 20-minute ride upstream following a tributary of the Changres River to visit the Emberá village of Parara Purú. As we motored up the river, men fished along banks with handlines for peacock bass, snook, and tarpon. Women and kids washed clothes in the river.

The headman dressed in a loincloth greeted us as the canoe ran ashore on the muddy bank of the small village. He welcomed us to climb the hill to join some of the 25 villagers sitting in the shade of a new ramada. “Bella”, a pet spider monkey played with diapered babies while bare-breasted women nursed babies.

The headman dressed in a loincloth greeted us as the canoe ran ashore on the muddy bank of the small village. He welcomed us to climb the hill to join some of the 25 villagers sitting in the shade of a new ramada. “Bella”, a pet spider monkey played with diapered babies while bare-breasted women nursed babies.

Historians believe that the Emberá migrated to Panama from the Amazon River in Columbia. They played a role in the construction of the Panama Canal by using their skills to hand carve canoes. In return, the Emberá were given land in Charges National Park. An hour and a half from the modern architecture of Panama City, the Emberá maintain their primitive style of life in the rainforest. Their thatched roofs open-air huts are built on stilts to protect from the river’s flooding. They subsist on corn (which they grow in a small plot) and fish the river. They sell woven baskets and carvings to the few visitors who made the canoe voyage upstream. Women paint their topless bodies with the black colored fruit of the Jagua (it looks like a dark henna.) Men hang out or tend to the needs of the village wearing loin clothes. The scene is reminiscent of villages in the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea.

Tulio and Ricardo want to show us some “nearby” waterfalls. Suddenly, I felt a small hand grab mine. Ronaldo, a 10-year-old boy had “adopted” me. Climbing in the dugout canoe, we motored a half-hour upriver through the rainforest. “It’s only a twenty minute walk to Cascada Bonita. They looked concerned about the Jagua tattoo just painted on my ankle. They indicated that we would be wading through streams and the tattoo would dissolve in the water. Hiding our shoes in some reeds, the twenty-minute walk for the Emperá took us more than an hour. They ran over sharp stones of the creek bottom that were painful to our bare feet. Scrambling over rocks, climbing muddy trails over hills descending down into the stream, we finally reach the waterfall. Our naked guides jump into the cool water of the pool at the base of the falls. Ronaldo did somersaults from a rock into the pool and climbed trees like a monkey. Having been advised to dress appropriately, we sat sweating on the rocks, our tired feet cooling in the water.

Tulio and Ricardo want to show us some “nearby” waterfalls. Suddenly, I felt a small hand grab mine. Ronaldo, a 10-year-old boy had “adopted” me. Climbing in the dugout canoe, we motored a half-hour upriver through the rainforest. “It’s only a twenty minute walk to Cascada Bonita. They looked concerned about the Jagua tattoo just painted on my ankle. They indicated that we would be wading through streams and the tattoo would dissolve in the water. Hiding our shoes in some reeds, the twenty-minute walk for the Emperá took us more than an hour. They ran over sharp stones of the creek bottom that were painful to our bare feet. Scrambling over rocks, climbing muddy trails over hills descending down into the stream, we finally reach the waterfall. Our naked guides jump into the cool water of the pool at the base of the falls. Ronaldo did somersaults from a rock into the pool and climbed trees like a monkey. Having been advised to dress appropriately, we sat sweating on the rocks, our tired feet cooling in the water.

The U.S. government used to operate a radar station in the rainforest about 45-minutes outside the city. When the cold war ended, the facility was used by drug enforcement to monitor traffic coming from Columbia. Several years ago, the government abandoned the tower. Raul Arias de Para saw an opportunity to use the tower, which was taller than the canopy of rainforest as a small lodge for bird watchers. Rising at daylight, birders could enjoy a close encounter with the birds and wildlife. The seven rooms (with shared bath) has been recognized as one of the top bird watching destinations in the world.

In Colon, I boarded the M. V. Sea Voyager, a Lindblad Expeditions ship headed north to Belize. But first the ship made a few more stops at remote destinations in Panama. We traveled south to the archipelago of San Blas. The ship, which traveled while we slept, stopping first at the village of Isla Grande(pop.1000) and then in the port of Portobello (both in Portobello National Park.)

In Colon, I boarded the M. V. Sea Voyager, a Lindblad Expeditions ship headed north to Belize. But first the ship made a few more stops at remote destinations in Panama. We traveled south to the archipelago of San Blas. The ship, which traveled while we slept, stopping first at the village of Isla Grande(pop.1000) and then in the port of Portobello (both in Portobello National Park.)

Traveling north, our journey followed the coastline of the Golfo de Mosquitos located between the eastern Caribbean and western Panama. Our final stop in Panama was the island of Escudo de Veraguas. Like Portobello, it too was discovered and named by Christopher Columbus, on his fourth and final voyage,

Panama’s Canal may be one of the great civil engineering wonders of the world, but the culture, history, geography, and people are still a well-kept secret. Visit Panama while it remains unspoiled.

If you go:

Panama Tourism (IPAT) www.panamtours.com or www.panamainfo.com 1-800-231-0568

Lindblad Expeditions 1-800-EXPEDITION (1-800-397-3348) or 212-765-7740 explore@expeditions.com or go to www.lindblad.com

Panama City Hotels:

Miramar Intercontinental www.intercontinental.com

Holiday Inn www.sixcontinetshotels.com

Resorts:

deCameron Hotel in San Carlos www.decameron.com or decavtas@pty.com

Gamboa rainforest resort www.gamboaresort.com gamboaresort@sinfo.net 1-877-800-1690

Charming Inns in El Valle: Park Eden Bed and Breakfast parkedne@cwpanama.net Rincon Vallero rinconvallero@sinfo.net or www.rinconvallero.com Canopy Adventure arba@pananet.com www.canopytower.com

Panama Canal

Written and photographed by Mary L. Peachin

In 1880, Frenchmen Count Ferdinand de Lesseps dreamed of building a sea level interocean canal. In Egypt the land was level so he was able to build a lock-type canal on the Suez. While the climate was extremely hot, there was water available.

In 1880, Frenchmen Count Ferdinand de Lesseps dreamed of building a sea level interocean canal. In Egypt the land was level so he was able to build a lock-type canal on the Suez. While the climate was extremely hot, there was water available.

He began work in Panama the following year and three years later, his labor force totaled 19,000 men. de Lesseps grossly underestimated the task at hand and in the next ten years would make little progress. 22,000 men succumbed to the ravages of yellow fever, typhoid fever, and malaria. By 1889, de Lesseps’ company, Compagnie Universell du Canal Interocéanique declared bankruptcy.

The United States, who had a vested geographically interest in the completion of the Canal studied the possibility of building the canal in Nicaragua, a country closer to the United States. After several years of study, President Theodore Roosevelt, concerned about numerous volcanic eruptions in Nicaragua, made the decision to buy the Canal from the French and Colombia, who at that time ruled Panama until its independence in 1903. Colombia received a payment of $25 million dollars at the signing to the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty.

The United States, who had a vested geographically interest in the completion of the Canal studied the possibility of building the canal in Nicaragua, a country closer to the United States. After several years of study, President Theodore Roosevelt, concerned about numerous volcanic eruptions in Nicaragua, made the decision to buy the Canal from the French and Colombia, who at that time ruled Panama until its independence in 1903. Colombia received a payment of $25 million dollars at the signing to the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty.

75,000 men and women spent 10 years building the Canal at a cost of almost $400 million.

Dr. William Crawford Gorgas assumed responsibility for the first challenge of the Canal. Discovering that epidemics of malaria and yellow fever was caused by the bite of the mosquito, he sought to eradicate them.

Another formidable challenge was the 8.5-mile Gaillard (Culebra) Cut. This treacherous section buried thousand in continual landslides. Chief Engineer Colonel George Washington Goethals tackled the excavation of this section.

Another formidable challenge was the 8.5-mile Gaillard (Culebra) Cut. This treacherous section buried thousand in continual landslides. Chief Engineer Colonel George Washington Goethals tackled the excavation of this section.

The 51.2 statute miles of the lock-type Panama Canal opened on August 15, 1914. Three sets of two-lane locks, Miraflores(on the Pacific side),Pedro Miguel, and Gatun Locks(on the Atlantic) lift ships almost 90 feet above sea level to the main body of water of Gatun Lake, then lower them back to sea level. Each lock chamber is 110 feet wide and 1,000 feet long. The water used to raise and lower vessels is fed by gravity from Gatun Lake into the locks.

In 1977 the Torrijos-Carter treaty was signed and the Panama Canal Authority became an autonomous governing body known as the Panama Canal Authority.