written and photographed by Mary L. Peachin

Mar 2003, Vol. 7 No. 6

“Secrets of the South Shore” bicycle tour along the rugged North Atlantic coastline of Nova Scotia sounded intriguing. What kind of secrets would Freewheeling AdventuresBicycling share with us?

“Secrets of the South Shore” bicycle tour along the rugged North Atlantic coastline of Nova Scotia sounded intriguing. What kind of secrets would Freewheeling AdventuresBicycling share with us?

Ten riders from the United States and Canada met in the seafaring town of Chester. The quaint fishing village, founded in 1759, is located about 45-minutes south of Halifax. Arriving late on a Sunday afternoon, locals sat in their vehicles, car doors opened while others reclined on lawn chairs as they listened to a late afternoon pop concert. A band struck up some oldies under the whitewashed gazebo next to the yacht club. Our base for the next two nights was The Captain’s House, a four-room inn. Visitors and locals mingle with houseguests to enjoy the fresh gourmet seafood served nightly.

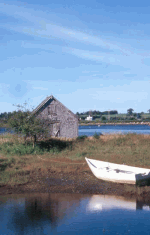

Our first day of the bicycle the secrets of the South Shore began to unravel as we rode the 40-mile-ish loop around the Aspotogan Peninsula. Goldenrod, Queen Anne lace, wild iris, roses and orchids, Black-eyed Susan, fireweed, and rosehips the size of cherry tomatoes lined the hilly two-lane road. Our bicycle route weaved through forests of spruce that seemed to separate beach-fronted fishing villages.

Our first day of the bicycle the secrets of the South Shore began to unravel as we rode the 40-mile-ish loop around the Aspotogan Peninsula. Goldenrod, Queen Anne lace, wild iris, roses and orchids, Black-eyed Susan, fireweed, and rosehips the size of cherry tomatoes lined the hilly two-lane road. Our bicycle route weaved through forests of spruce that seemed to separate beach-fronted fishing villages.

By the time we had cycled about 25-miles to Mahone Bay we discovered that “keeping up with the Jones” in this part of Nova Scotia is a homeowners pride of their garden. Lawns were covered with white hydrangeas, homes sparkled with recently painted red, green, purple or yellow shingles. Beaches at Blandford ( a former whaling station) and Bayswater may have been a chilly 60-degrees, but the locals swimming in the surf took advantage of a sunny day. Nearby, passersby stopped at a flower filled memorial to pay tribute to the victims of a Swiss Air 111 flight.

Stopping for a picnic lunch in Bayswater Park, we noticed that Freewheeling’s secret was shared in part with other cyclists. With more than 4,625 miles of coastline in Nova Scotia, Backroads, a US bicycling touring company and Canadian Bicycling were sharing the same picnic site.

Fresh flowers adorned our picnic table complimented by colorful china plates and linen napkins. The buffet lunch included a whole smoked salmon plus homemade olive tapenade, humus, chutney, and salmon pate. Freewheeling’s owner Philip Guest believes the coffee he serves his guests should be freshly roasted and hand ground. In fact, the coffee grinder was attached to the picnic table and served in espresso cups.

Fresh flowers adorned our picnic table complimented by colorful china plates and linen napkins. The buffet lunch included a whole smoked salmon plus homemade olive tapenade, humus, chutney, and salmon pate. Freewheeling’s owner Philip Guest believes the coffee he serves his guests should be freshly roasted and hand ground. In fact, the coffee grinder was attached to the picnic table and served in espresso cups.

Freewheeling, based in nearby Hubbards, knows the Maritimes and Atlantic Canada well. Their guides are local and knowledgeable, daily schedules are less structured. Guests can vary their route and there seem to be more flexibility than the itineraries offered by larger cycling companies. There is no morning “route rap” and while daily instructions and maps can sometimes be confusing, that’s part of a Freewheeling adventure.

It was a stroke of coincidence that we ran into Bucky (Arnold) Harnish, and his mates, Wayne and Ozzie, as we rode past a dock in Mill Cove. They were boarding their trawler, “Capt. Pooch M & T”, to boat out to check their tuna trap. Asking if we could join them, we watched as the three, beers in hand, joyously celebrated the morning’s catch of a 250-pound tuna. If they were lucky, the fish would fetch $20 a pound and already be on a flight to Japan to be sold for sushi. The summer had yielded few monster-size fish. In the past they would have fattened up the tuna before shipping it off so the additional weight fetched more money, but times are leaner now. If a tuna gets caught in the maze-like trap which descends to the bay’s bottom at 95 feet and is anchored to the shore about 1/4 mile away, they shoot the fish and tow it to a nearby air strip across the bay. Bucky has caught fish weighting more than 1000 pounds during the two-month tuna season (he traps lobsters during their open season months).

It was a stroke of coincidence that we ran into Bucky (Arnold) Harnish, and his mates, Wayne and Ozzie, as we rode past a dock in Mill Cove. They were boarding their trawler, “Capt. Pooch M & T”, to boat out to check their tuna trap. Asking if we could join them, we watched as the three, beers in hand, joyously celebrated the morning’s catch of a 250-pound tuna. If they were lucky, the fish would fetch $20 a pound and already be on a flight to Japan to be sold for sushi. The summer had yielded few monster-size fish. In the past they would have fattened up the tuna before shipping it off so the additional weight fetched more money, but times are leaner now. If a tuna gets caught in the maze-like trap which descends to the bay’s bottom at 95 feet and is anchored to the shore about 1/4 mile away, they shoot the fish and tow it to a nearby air strip across the bay. Bucky has caught fish weighting more than 1000 pounds during the two-month tuna season (he traps lobsters during their open season months).

Jumping back on our bicycles, we finished our ride in Hubbards Cove before vanning back on the highway to Chester. Continuing south on our 27-speed Trek hybrids we continued to follow the Lighthouse Trail (which doesn’t pass directly by many lighthouses) around Mahone Bay to Lunenburg.

Jumping back on our bicycles, we finished our ride in Hubbards Cove before vanning back on the highway to Chester. Continuing south on our 27-speed Trek hybrids we continued to follow the Lighthouse Trail (which doesn’t pass directly by many lighthouses) around Mahone Bay to Lunenburg.

Along the road we stopped to watch Bill Lutwick restore wooden boats in his traditional shop. At a “whale carvings sign, we met Peter Redden. His father passed down the craft to his son who now carves sharks and penguins rather than the whales that brought local fame to his father. At the Innlet Cafe in Mahone Bay, the burger was made from fresh Digby scallops. The restaurant buys mussels right off the fisherman’s boat.

Settled in 1753, Lunenburg was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. The port city, built on a hillside was once a fishing and shipbuilding center. The Bluenose schooner (preserved on the back on the Canadian dime) was built here in 1921. The town received notoriety for his rum-rumming trade during the 1930s.

Our quads screamed on a “monster” hill on the outskirts of Lunenburg. We followed a peninsula winding around a golf course. A glimpse behind was a landscape of the colorful wharf front of Lunenburg.

Our quads screamed on a “monster” hill on the outskirts of Lunenburg. We followed a peninsula winding around a golf course. A glimpse behind was a landscape of the colorful wharf front of Lunenburg.

Along the way, we stopped at Ovens Natural(privately owned) Park. A path high above the slate covered beach was the location of Nova Scotia’s brief 1861 gold rush. A cable ferry motored us from the peninsula to LeHave, where we stop for lunch in the village’s well-known bakery.

One of the highlights of our Lunenburg visit was a boat tour with the Lobsterman. While lobster fishing was not in season, Captain Barry Levy hydraulically hoisted six traps out of the bay as mate Jason Greek told us just about everything there was to learn about the tasty delicacy. In order to run these hour and half tours, the Lobsterman has an agreement Canada’s Department of Fisheries to tag the shellfish in order to trace their migration. Today, most lobstermen used metal traps that better withstand the winter water conditions. Levy referred to the older wooden variety, frequently displayed on house lawns for sale as “tourist” traps. Each trap they lifted had as many as half a dozen lobster weighing up to three pounds.

After a van transfer to Crescent Beach, we continued south along Lighthouse Route passing over one-lane iron bridges then winding back to Broad Cove, Little Harbour, and Mill Village. In the early afternoon we stopped to enjoy another gourmet picnic at Geese Haven, a privately owned park along the road.

After a van transfer to Crescent Beach, we continued south along Lighthouse Route passing over one-lane iron bridges then winding back to Broad Cove, Little Harbour, and Mill Village. In the early afternoon we stopped to enjoy another gourmet picnic at Geese Haven, a privately owned park along the road.

Our final night was spent at the rustic (built in 1928)White Point Beach Resort. We fell asleep listening to the crashing waves, our windows opened to hear the North Atlantic. Our final day was spent hiking the beach in Kejimkujik National Park. Deer and black bear dig insects from seaweed left on the beach at low tide. The endangered piping plover nests on this beach, harbor seals colonize along shoreline rocks.

The six-day freewheeling trip allowed Guides Patrice Cameron and Sabina Bauch to share their love and enthusiasm for their native province. Brief as it may have been, we all came away with the feeling of friendly people, beautiful landscapes and a curiosity to explore more of Nova Scotia.

The six-day freewheeling trip allowed Guides Patrice Cameron and Sabina Bauch to share their love and enthusiasm for their native province. Brief as it may have been, we all came away with the feeling of friendly people, beautiful landscapes and a curiosity to explore more of Nova Scotia.

For further information:

Freewheeling Adventures 1-800-672-0775 or (902) 857-3600 or www.freewheeling.ca

Kaulbach House Historic Inn (902) 634-8818 [email protected]

Hillcroft Cafe (92) 634-8031 www.bbcanada.com/1369.html or [email protected]

Ovens Natural Park (902) 766-4621 or www.ovenspark.com

Lobsterman Tours (902) 634-3434 or www.lobstermantours.com

The Lobsterman Tour

Written and photographed by Mary L. Peachin

While planning our late summer Freewheeling bicycling tour along the south coast of Nova Scotia, the image of lobster kept popping into mind. After our arrival, we learned that lobster was “out of season.” Fortunately, the third day of our bicycle trip we overnighted in the historic village of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, a town built in 1753 and designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

While planning our late summer Freewheeling bicycling tour along the south coast of Nova Scotia, the image of lobster kept popping into mind. After our arrival, we learned that lobster was “out of season.” Fortunately, the third day of our bicycle trip we overnighted in the historic village of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, a town built in 1753 and designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It was there that I caught a glimpse of a brochure offering the Lobsterman tour. Arriving late in the afternoon, I was not optimistic when I called to see if any tours were operating. “Yes, there is one at four, about 20-minutes from now.” We had just bicycled 40 miles from the village of Chester and all I could think about was a hot shower. “I’ll call back in a few minutes and see if I can make it down to the wharf in time.â€

It was well worth the quick shower and hustle to the pier.

Although lobster fishing was not in season, Captain Barry Levy offers the tour as part of a study he is doing for the Canadian Department of Fisheries. Levy hydraulically lifted six traps out of the bay, while his mate Jason Greek told us just about everything there was to learn about the tasty delicacy.

After tying each claw with a rubber band (to avoid a painful bite), Greek measured the size, check the sex, and then tagged (inserted into the carapace) the lobster to note the location where it was trapped. Greek also showed us other species found in their traps: periwinkles, rock crabs and the inedible non-native green crab, a stowaway on the hull of an inbound ship that has since become a prolific nuisance in these waters.

After tying each claw with a rubber band (to avoid a painful bite), Greek measured the size, check the sex, and then tagged (inserted into the carapace) the lobster to note the location where it was trapped. Greek also showed us other species found in their traps: periwinkles, rock crabs and the inedible non-native green crab, a stowaway on the hull of an inbound ship that has since become a prolific nuisance in these waters.

Displaying a trap, Jason told of the necessity of boxing the herring bait to prevent seals from stealing it. The savvy pinnipeds have even learned how to open the traps, which are now closed with bungee cord.

Lobster will explore the scent of the herring bait for about 8-9 minutes, and either finds the opening door of the trap or loses patience and crawl away.

The top part of the trap where the lobster feed is called the “kitchen” and the bottom; the area where they become trapped is the “parlor.” There are small “escape hatches” for undersized lobster. Traps cost about $60.00 and the new metal ones can last 8-10 years.

Included in our anatomy lesson were sexual parts of the crustacean. A female carrying roe is illegal to trap. She will carry 40-50,000 eggs for 9-10 months before releasing them to float to the surface. Less than 1% survive to maturity.

Lobster feed on sea urchin, crab, and fish. Once a year they molt (ecdysis) hiding in rocks while they shed their shell. They are vulnerable prey during this period. Greek also showed us several varieties of scallops and described how commercial vessels use chain mesh nets lined with tires to drag the ocean bottom. Scallops are still removed by hand from their shells.

Lobster feed on sea urchin, crab, and fish. Once a year they molt (ecdysis) hiding in rocks while they shed their shell. They are vulnerable prey during this period. Greek also showed us several varieties of scallops and described how commercial vessels use chain mesh nets lined with tires to drag the ocean bottom. Scallops are still removed by hand from their shells.

Today most lobstermen used metal traps because they can withstand rugged winter water conditions better than the wooden ones. Levy referred to the older wooden variety, which were made from spruce trees and bowed while wet, now frequently displayed “for sale” on house lawns as “tourist traps”.

During our trip, Levy’s fourth of the day, each trap had as many as half a dozen lobster weighing up to three pounds. The largest lobster Levy has trapped has been 12 pounds. He knew of one caught in Boston weighing 37 1/2. pounds.

Summer tours may be fascinating, but when the season in Lunenburg comes the last Monday in October (lasting until the end of May) Levy and Greek, who each own permits, fish in rough water starting before dawn returning to port after sunset. Their working day is a good 14 hours, they leave and return in the dark. In addition to hauling in traps, they have to freshly bait and maintain the traps. It’s hard but lucrative work. Licenses can’t be purchased. They might be available for sale but cost $100,000 to half a million dollars. Most permits are inherited and kept in the family. There won’t be any new permits added to the existing 40 districts of the Maritimes.

Fortunately, the lobster population is healthy, the regulations very strict, and to be there during the “season”, well, one might eat lobster for every meal. Lucky for us, some restaurants get lobster shipped from whichever district is in season. Lobsterman Tours (902) 634-3434 or www.lobstermantours.com