Written and photographed by Yvette Cardozo

Vol. 10 No. 4

Many people are familiar with the North and South Rims, but there is so much more to the Grand Canyon. West of the more popular spots is Havasu Canyon, and it’s a completely different world. From the top at Hualapai Hilltop, the entire Havasu rift spreads before you in a landscape of red and beige.

Many people are familiar with the North and South Rims, but there is so much more to the Grand Canyon. West of the more popular spots is Havasu Canyon, and it’s a completely different world. From the top at Hualapai Hilltop, the entire Havasu rift spreads before you in a landscape of red and beige.

Few people realize the immensity of the Grand Canyon’s 600 side canyons … and waterfalls—tall ribbons of frothing water dropping into shimmering, travertine laced blue-green pools make Havasu one of the Canyon’s most spectacular.

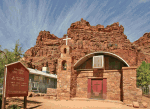

Unlike the rest of the uninhabited Grand Canyon, the village of Havasupai, located in the depths of the Canyon is home to 300 Native Americans, hunters and farmers removed from the rest of the world until the last century. Today, their livelihood has grown into a thriving tourist business. They provide services for hikers: renting campsites, operating a small lodge, and packing in their gear by mule and horse.

Though the villagers now enjoy modern conveniences like electricity, phone service, running water and a post office, they still treasure their past. Classes in the school are bilingual: their native Yuman dialect and English.

Though the villagers now enjoy modern conveniences like electricity, phone service, running water and a post office, they still treasure their past. Classes in the school are bilingual: their native Yuman dialect and English.

No trek into the Grand Canyon is just another stroll. From the rim, there is a 1,500 foot descent in a short mile and a half along a steep series of switchbacks cut through walls like a colorful geode of beige Coconino sandstone, red shale, then more sandstone.

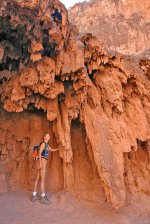

After several miles, the trail is less steep and more spectacular. The surrounding walls become closer with deeper shades of red becoming iron red limestone in a collection of fantastic shapes … soft round bulbs, sharp leaning slabs, narrow spires and wide towers. Cottonwoods grew in the deepest part of the ravines … huge ancient trees with wide canopies and gnarled five-foot trunks.

After several miles, the trail is less steep and more spectacular. The surrounding walls become closer with deeper shades of red becoming iron red limestone in a collection of fantastic shapes … soft round bulbs, sharp leaning slabs, narrow spires and wide towers. Cottonwoods grew in the deepest part of the ravines … huge ancient trees with wide canopies and gnarled five-foot trunks.

As narrow walls towered hundreds of feet above us, mineral deposits mixed with algae dripped in black streaks along with white lines of calcium carbonate. Although we were descending all day, this was not an easy hike. The trail alternated between loose scree and powdery red sand; so soft, it was like walking in water.

Three miles into the 10-mile hike, my boots crumbled, the soles peeling off completely at the toes. We wound duct tape around the whole mess and I slogged on, actually making it into camp and back out two days later on those poor boots.

Three miles into the 10-mile hike, my boots crumbled, the soles peeling off completely at the toes. We wound duct tape around the whole mess and I slogged on, actually making it into camp and back out two days later on those poor boots.

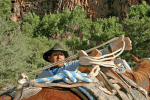

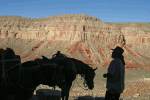

Along the trail, the sun was relentless. “Each of you needs to carry 100 ounces of water,” Arizona Outback Adventure leader Brian Jump tells us. And he was right. I drained every drop. Every so often, as we threaded narrow cuts, we’d hear someone yell, “Horse!” And around a bend, half a dozen ponies came through, nimbly picking their way across rocks or, on a sandy open flat, galloping in a cloud of dust.

Virtually everything is delivered to Havasupai by horse or mule including hiker packs, grocery supplies for the village store, and construction material for village houses.

The public campground is a scene of contrast—a mix of diehards with single bivy sacks and freeze dried lasagna blend with folks who paid to pack-in arriving with camp chairs, full size Coleman stoves, queen-size air mattresses, hammocks and huge coolers. Our camp included a dozen walk-in tents by a river, shaded by cottonwood trees, well away from the public tent grounds.

The public campground is a scene of contrast—a mix of diehards with single bivy sacks and freeze dried lasagna blend with folks who paid to pack-in arriving with camp chairs, full size Coleman stoves, queen-size air mattresses, hammocks and huge coolers. Our camp included a dozen walk-in tents by a river, shaded by cottonwood trees, well away from the public tent grounds.

Dinner was carried in a dozen huge plastic coolers unloaded from the horses along with our packs. Quite a feast to be served in the Grand Canyon: lemon grilled halibut, two kinds of chicken, steaks and teriyaki asparagus spears followed by cheesecake.

Dinner was carried in a dozen huge plastic coolers unloaded from the horses along with our packs. Quite a feast to be served in the Grand Canyon: lemon grilled halibut, two kinds of chicken, steaks and teriyaki asparagus spears followed by cheesecake.

After a night’s sleep, we hiked to Mooney Falls, named after an early prospector. In 1880, Mooney had the misfortune of lowering himself over a 200-foot waterfall with only 150 feet of rope. Some months later, prospectors found his body, totally encased in travertine … the same calcium carbonate/magnesium chloride mix that colors the water, forms pool rims and leaves stalactite-like drips across the waterfall walls. We approached the pool from the top, peering over the rim at a 20-story drop of dripping, sharp points. And we had to climb down it.

The first part of the trail is carved into steep stairs winding through two tunnels before opening to an exposed rock face … a vertical expanse of chains, slippery foot holds and slick wood ladders follows. For someone with a fear of heights, it is a major adrenaline rush.

The first part of the trail is carved into steep stairs winding through two tunnels before opening to an exposed rock face … a vertical expanse of chains, slippery foot holds and slick wood ladders follows. For someone with a fear of heights, it is a major adrenaline rush.

At the bottom, we swam a bit, photographed a lot and then headed farther down the canyon to more pools and a rope swing. The really talented folk did back flips off the end of the rope. The rest of us crashed in the mother of all belly flops.

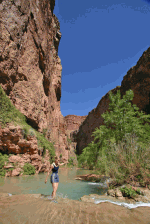

On our easier return, we stopped to admire a side canyon whose deep red walls appeared to glow in reflected light. After a break for a late lunch, we headed to the canyon’s namesake, Havasu Falls.

Wider than Mooney, the falls flow through a cut in the wall before dropping into a glacial blue pool. It was a landscape of travertine benches and small waterfalls flowing from one pool to another. But most spectacular was the 300-foot-wide wall itself. Flowing sheets of smooth rock angled off the main wall, hanging suspended in mid air and ending in jagged, dripping edges.

Wider than Mooney, the falls flow through a cut in the wall before dropping into a glacial blue pool. It was a landscape of travertine benches and small waterfalls flowing from one pool to another. But most spectacular was the 300-foot-wide wall itself. Flowing sheets of smooth rock angled off the main wall, hanging suspended in mid air and ending in jagged, dripping edges.

Our final day, we headed back to the village, located a couple of miles before the camp. Along the way we stopped to admire Navajo Falls … short and wide, the water surrounded by cottonwoods and maidenhair ferns. It looked like a landscape of Hawaii … except the water was quite cold.

Returning to the village, a helicopter waited to lift us out of the Canyon. It’s a five minute flight instead of a six hour plus upward slog. And it’s a chance to get an incredible bird’s eye view of the journey. As we waited to load, some of us scribbled post cards and mailed them from the Supai post office … the last post office in the US served by mule. Then, we sat around a large grassy field sucking ice pops as three yearling horses galloped through town trailing a pack of barking dogs in their wake.

Returning to the village, a helicopter waited to lift us out of the Canyon. It’s a five minute flight instead of a six hour plus upward slog. And it’s a chance to get an incredible bird’s eye view of the journey. As we waited to load, some of us scribbled post cards and mailed them from the Supai post office … the last post office in the US served by mule. Then, we sat around a large grassy field sucking ice pops as three yearling horses galloped through town trailing a pack of barking dogs in their wake.

If you go:

Havasu Canyon lies west (about 40 miles) of the more popular South Rim, at the termination of the 63-mile Indian Route 18, about 160 miles northwest of Flagstaff, AZ.

Prime hiking season is spring (April/May) and fall (September/October). Temperatures reach well over 100 degrees in mid summer. The descending hike to camp is 10 miles, and takes more than six hours. Take plenty of water and sturdy boots.

If you are doing the trip on your own, a camping permit is required. Call Havasupai Tourist Enterprise at 928.448.2121. The cost is $20 to enter the village, $10 per person per night for camping, and $150 per pack horse roundtrip, which will cover gear for two people. The flight out is $85 per person.

An easier option is Arizona Outback Adventure (AOA) guided four or five day hike which includes the logistics of transportation, gear, pack ponies and chopper. The trip includes van transportation from Phoenix or Scottsdale, AZ, camp gear and fees, food and guided hikes.

Four-day trips in 2006 will run $1,425; five day trips are $1,625. The trips run from mid March through late July, then September through late October. Contact Arizona Outback Adventures, 866.455.1601, or www.aoa-adventures.com.