by Yvette Cardozo and Bill Hirsch with photography by Yvette Cardozo, Greg Seymour and CC Africa

Aug 2004, Vol. 8 No. 10

The night was pitch black; we didn’t expect to see much of anything. Suddenly, in the beam of our hand lamp, we spotted fresh tracks with patches of fur scattered on the ground followed by spots moving through the brush.

The night was pitch black; we didn’t expect to see much of anything. Suddenly, in the beam of our hand lamp, we spotted fresh tracks with patches of fur scattered on the ground followed by spots moving through the brush.

A young leopard had recently birthed and was hungrily in search of prey. As we watched, she dropped to a crouch hiding behind a bush. A high pitched scream reverberated through the air. The brush shook as the new mother emerged with a small, squirming deer-like duiker in her mouth.

Ranger guide Greg Seymour warned, “her cry will attract other predators.” Within minutes, a hyena crept out of the shadows and sprang for the duiker. Not willing to share her prey, the leopard leaped into a tree, the duiker still in her mouth. Finally, satiated and exhausted, she jumped to a higher branch, wedged the kill into a notch, sprawled her body across it and went to sleep.

We had only spent two hours at the South African safari lodge of Londolozi, and had already witnessed a scene out of National Geographic. Game parks have been part of South Africa for a century. But today, a decade after the abolishment of Apartheid, the experience is quite special.

We had only spent two hours at the South African safari lodge of Londolozi, and had already witnessed a scene out of National Geographic. Game parks have been part of South Africa for a century. But today, a decade after the abolishment of Apartheid, the experience is quite special.

Lodges range from tents to luxury encampments on bluffs overlooking magnificent scenery. Beyond the standard Land Rover ride, you can hike, mountain bike, even ride horseback to view animals.

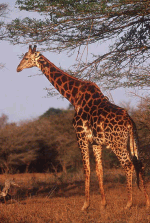

One afternoon we wandered to Phinda’s watering hole. Searched in vain for cheetahs, instead we spotted a vervet monkey atop a tree, zebras, wildebeests, warthogs, a giraffe, two white rhinos, some lions and a bull elephant. Not bad for a single afternoon.

When we reached the watering hole, the animal siting was fascinating. A herd of 30 adult elephants including several babies and adolescents wandered out of the trees. After one of those hot summer days, it was apparently play time

Huge males siphoned gulps of water into their trunks, then poured it into their mouths, gallons at a time. At the far end of the hole, others wallowed in mud, rolling and caressing one another with their trunks. Closer to us, two females waded, their two calves tucked under their stomachs. All that was visible were legs and tiny trunks.

The pack bathed and played for more than an hour. Suddenly, they submerged in the mud wading into deeper water to splash and playfully sparred with one another. Low rumbling calls, slurping and the click of tusks sounded when two young males play charged each other. Another elephant rolled completely in the water, his huge feet surfacing. Others dived under, leaving only their trunks on the surface like submarine periscopes. They all seemed so absolutely happy … a fine day at the beach.

The pack bathed and played for more than an hour. Suddenly, they submerged in the mud wading into deeper water to splash and playfully sparred with one another. Low rumbling calls, slurping and the click of tusks sounded when two young males play charged each other. Another elephant rolled completely in the water, his huge feet surfacing. Others dived under, leaving only their trunks on the surface like submarine periscopes. They all seemed so absolutely happy … a fine day at the beach.

On the other bank, a pride of lions, eyeing the herd they did not considered predation. As suddenly as they arrived, the elephants clambered out of the water and, as the last rays of light faded, filtered back into the forest.

So many animals, effortless viewing, we got to wondering…

So many animals, effortless viewing, we got to wondering…

Yes, we were in a managed park, but it wasn’t like Disney or the depths of the Congo. Occasionally, we saw a fence … the edge of the park. During the night at Phinda, we could see lights of cell phone towers in the distance. Because of an ongoing drought, the rangers were pumping water into two water holes and hauling bales of hay in for the animals.

These animals are used to the vehicles and virtually ignore them. At times, we were just yards from lions, leopards, cheetahs, giraffes and elephants while they drank, lazed in the sun, fed on fresh kill.

“There aren’t many truly natural situations in South Africa, said Phinda Ranger Phill Steffny. “Even in Kruger Park, which is five million acres, eventually you will see a fence. We have to manage the land and because the animals can’t migrate the way they would in the wild.”

“There aren’t many truly natural situations in South Africa, said Phinda Ranger Phill Steffny. “Even in Kruger Park, which is five million acres, eventually you will see a fence. We have to manage the land and because the animals can’t migrate the way they would in the wild.”

“But, never forget these are wild animals,” Steffny warned. There is no walking alone around camp at night. After sundown, even trips between the campfire and our tent at Phinda and from the lodge deck to our rooms at Londolozi were escorted. And we carried a gun in the Land Rover.

Another surprise was that this part of South Africa was not tropical. No dense, fern and vine choked jungle. South Africa is sub-tropical and its game parks sit on sandy scrubland. Phill swears there are hundreds of varieties of trees, but from the back of a Land Rover, they all look the same … mostly acacias with thin trunks, small olive leaves, and nasty thorns. Open prairies were covered with a golden grass studded with clumps of palmetto palms. And there’s a dryness to it all, borne out by the occasional cactus.

Another surprise was that this part of South Africa was not tropical. No dense, fern and vine choked jungle. South Africa is sub-tropical and its game parks sit on sandy scrubland. Phill swears there are hundreds of varieties of trees, but from the back of a Land Rover, they all look the same … mostly acacias with thin trunks, small olive leaves, and nasty thorns. Open prairies were covered with a golden grass studded with clumps of palmetto palms. And there’s a dryness to it all, borne out by the occasional cactus.

The schedule at a game park hasn’t changed much over the years. We headed out at dawn and dusk to view animals, usually riding in an open Land Rover (the safari vehicle of choice) with the ranger at the wheel and the tracker in a seat on the hood. What has changed is the number and quality of the parks and the lodges.

“In 1985 there were maybe 80 game parks in South Africa and now there are 400,” said Yvonne Short, operations director for CC Africa, which runs 15 safari lodges across Africa.

“In 1985 there were maybe 80 game parks in South Africa and now there are 400,” said Yvonne Short, operations director for CC Africa, which runs 15 safari lodges across Africa.

Phinda was farmland before 1991 (when the government changed). It was pineapples, cotton, sisal fields, and a lot of cattle and sports hunting. But a century ago, this land teemed with animals and the goal is to reintroduce those animals to the area.

One or two of the new park lodges are simple tent camps, but most are quite luxurious, with individual decks, outdoor “plunge pools” (like hot tubs without the heat or jets) and incredible menus. Londolozi was voted best small hotel in the world by Travel & Leisure. Not best safari lodge … best small hotel, period.

Many lodges overlook rivers or grassland with amazing opportunities to see animals literally at your door. We arrived at Londolozi’s Bateleur Camp to find elephants nibbling on riverbank trees just below our deck. Guests enjoying tea at another CC Africa Lodge watched a cheetah take down a duiker, then call her cubs in for dinner.

Many lodges overlook rivers or grassland with amazing opportunities to see animals literally at your door. We arrived at Londolozi’s Bateleur Camp to find elephants nibbling on riverbank trees just below our deck. Guests enjoying tea at another CC Africa Lodge watched a cheetah take down a duiker, then call her cubs in for dinner.

But it’s also about service. For an extra fee, your group can have a private Land Rover and remained out viewing all day. Miss breakfast? No problem. The ranger calls the lodge, you wheel around a grassy hill and find a lodge chef scrambling mushroom omelets over a camp stove.

As for us, we got up early our last day and found eight Cape buffalo grazing on the camp’s front lawn and hippos snorkeling in a water hole. We drove to the tree where the leopard had taken her kill the night before but she was gone and so were all signs of her prey. A radio call came in that a leopard had been spotted and we rushed to the scene … not to find the leopard but to find an extremely rare pack of wild dogs hunting. They’ve got calico cat-like markings, long, graceful legs and a memorable stink.

As for us, we got up early our last day and found eight Cape buffalo grazing on the camp’s front lawn and hippos snorkeling in a water hole. We drove to the tree where the leopard had taken her kill the night before but she was gone and so were all signs of her prey. A radio call came in that a leopard had been spotted and we rushed to the scene … not to find the leopard but to find an extremely rare pack of wild dogs hunting. They’ve got calico cat-like markings, long, graceful legs and a memorable stink.

The leopard, the same female, was waiting for us under a bush. She groomed herself, stretched in a long, slow, toothy yawn, curled up and went to sleep. We hung around, shooting several rolls of film, then, on the way back to the lodge, saw a cheetah.

And so, in the end, we had not only saw the Big Five (lion, leopard, buffalo, elephant and rhino) but also the Magnificent Seven(wild dogs and cheetah).

TIDBIT INFO

Going on safari is, of course, all about viewing animals. But it is also about learning. Among our more intriguing discoveries:

* Prey animals don’t sleep like people. Not ever. “They do lie down to rest their legs and bodies,” said Ranger Phill Steffny. “sleep would put them at serious risk.” This involves all animals that get eaten: impalas, wildebeests, nyalas, zebras, and buffalo.

Lions, on the other hand, sleep 20 hours a day, which shows you just who is on top of the food chain.

* Giraffes browse from tree to tree, moving into the wind because the trees are actively trying to avoid being eaten. How? As the giraffe nibbles, the tree raises the tannin levels in its leaves, making the leaves bitter. The giraffes feed into the wind because the trees send out pheromones (which travel on the wind) to warn other trees to raise their tannin levels).

* The fabulous leopard viewing at Londolozi can be traced back to a single female leopard in 1979 who was the first to tolerate vehicles. She had nine litters, all of whom were raised with Land Rovers around. Now, five generations later, leopards allow vehicles to follow them through thick brush as they make kills or travel to their cubbing dens.

* Elephants can talk to other elephants as far as five miles away by using an ultra low frequency rumble that people can’t hear. It’s similar to the way that whales communicate over long distances. Elephants have extremely inefficient digestive systems, meaning they have to eat a lot to get enough nutrition to live. The average elephant eats 60-70 lbs. of leaves and branches a day, much of which comes out looking almost like it did when it went in.

INFO BOX

Game viewing in South Africa is good year round. Winter is cooler and more comfortable than mid summer but it can become uncomfortably chilly at night with temperatures in the 30s or 40s. Mid summer can be very hot with temperatures rising above 100 F. Most lodges have plunge pools or swimming pools. Because of the heat, tent camps tend to close in mid summer.(December – February).

For more information on safari camps, contact CC Africa (Conservation Corporation Africa) at 888/882-2742 or www.ccafrica.com.